When we were together, when we saw each other, when we smiled, when we met, when we talked, when we said hello or goodbye, when we shared, when we were one, when I kissed you,

when you kissed me, when I loved you, when you loved me…

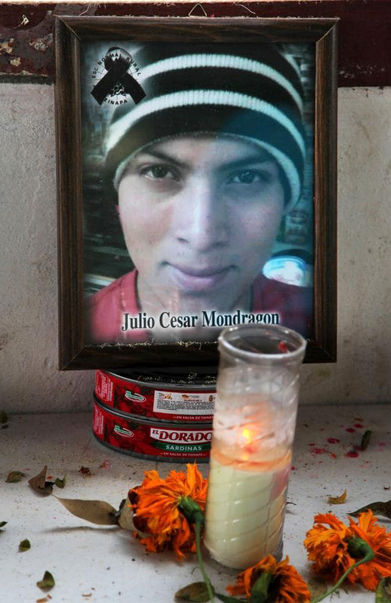

“I’m gonna love the day I graduate, because you and my daughter will go pick me up. The three of us will walk out of there.” Julio César Mondragón Fontes dreamed out loud. As a child he was educated by his mother, Aphrodita, who had received a degree in primary education: "Bravo, bravo, you did it!,” she said cheerfully to her boy. It was a shared dream that lasted beyond childhood. Julio César knew that studying was the only way he and his family could escape poverty, and was always clear that he wanted to be a teacher, like almost all his uncles, aunts and cousins.

Julio César grew up in San Miguel Tecomatlán, two hours from Mexico City. He and his younger brother Lenin were raised by their mother, in an extended family environment of grandparents, uncles, and cousins. His grandfather taught him to sow and harvest avocado. He helped his mother make floral arrangements for school events, party halls or for the neighborhood church. He sold chocolates and sugar candies, labored as a masonry assistant, prepared the firewood to cook the pork rinds that his mother sold and also worked for a time as a security guard. At a very young age he was already aware of family economic deprivation, so he demanded nothing.

Mondragón Fontes is a family of progressive ideas. Julio César was a lover of writing and philosophy, and was talkative and creative. He always carried a notebook that he was constantly writing and drawing in. He liked to run and walk through the mountains, especially in the rain. At some point his mother came to think that his real profession would be a runner or archaeologist, because he collected pre-Hispanic objects, clay necklaces and old-looking things he found on his walks.

Julio César studied for a year at the Normal de Tenería, in Tenancingo. It was here, at a school dance in 2010, that he met Marissa Mendoza Cahuantzi, who was also studying to be a teacher. It seemed like Julio César was on the path he envisioned for himself. His grandmother Guillermina had played a key role in his unbringing, and when she passed away Julio César was devastated. Poor attendance cost him his scholarship, forcing him to seek education elsewhere.

He tried to enroll in the Normal Rural of Tiripetío, Michoacán, but did not pass the exam, and was later accepted in the Ayotzinapa Rural Teachers’ College. By this time, Julio César and Marissa were married, living in Mexico City, and about to welcome their first child. They had also planned out the rest of their lives: work hard, buy a house, build a family, grow old together.

"The last thing he said to me [before leaving], was that he was going to that school, and he was going to leave a mark.”

Admission into Ayotzinapa meant that Julio César would be separated from his family for most of the four-year educational program, which was very difficult for them. He wrote Marissa a letter in which he said that the saddest thing for him was not having a father, and that he did not want his daughter to live with the same absence. Three weeks after he moved to Guerrero to begin his studies, on July 30, Marissa gave birth to their daughter, Melisa Sayuri. Julio César and Marissa last saw each other on September 11, 2014. He was given a pass by the school to travel to Mexico City to see his newborn daughter for the second time. He had only been able to spend 15 days with the daughter he waited so long to meet.

On the night of September 26, Julio César was on one of three buses of students that were ambushed and attacked by municipal police at the intersection of Juan N. Álvarez and Periférifo Norte in Iguala. At some point he contacted Marissa, and told her that the police were shooting at them. She told him to get out of there, to take care of himself, to think about his daughter, to think about them. He replied that he would not, that he could not leave his classmates. They remained in contact until he sent her a last alarming message: “I ask that you take good care of my daughter, and yourself. Don't forget that I love you both, because they are probably going to kill me.”

At approximately 11:30, after the first attack at Juan N. Álvarez and Periférifo Norte, in which approximately 20 students from the third bus were driven away in police vehicles, remaining students posted lookouts and placed rocks and articles of trash around the gun shells and bloodstains left behind in an effort to protect the crime scene. Soon, two vans of students arrived from Ayotzinapa , in response to distress calls from classmates, and a few journalists and residents began to appear. Julio César was taking pictures and recording video as the students were preparing to hold a news conference at 12:30 with reporters and professors of the CETEG (State Coordinator of Education Workers in Guerrero.) Gunmen arrived in vehicles and fired at close range from automatic weapons, killing Daniel Solís Gallardo and Julio César Ramírez Nava, and injuring Edgar Andrés Vargas, in addition to journalists and students who were running to safety. These were the last moments anyone would see Julio César. His body was found in the early morning hours the next day on a dirt path in an industrial area less than a mile from where he disappeared, recognizable only by scars on his hand, and the black scarf he was wearing that Marissa had knitted for him.

Julio César had been pursued as he ran. He struggled, fought and defended himself against his aggressors and died from head trauma after being tortured, severely beaten, and mutilated. His autopsy revealed 64 fractures in 40 bones. The manner of his death and the tainted investigation that followed would shine a spotlight on endemic corruption and impunity.

“This isn’t a typical farewell letter. I beg you never to forget me, remember I love you with all my heart. Only hope can nourish the seeds of the future. Tell my daughter how much her Daddy loves her, even if he’s gone. Take good care of her and giver her all the love I wanted so much to give her. When she asks about me, tell her I’ll always be with her. I don’t know if I’ll be back from where I’m going. My dreams scare me a lot, but I want you to know that wherever I go, you and the baby will be there with me. Whatever happens, don’t look back, and don’t look down, keep your head up and never lose hope.”

- Julio César Mondragón Fontes, to his wife Marissa.

The last letter he ever wrote was found in his notebook after his death.

Julio César was full of emotions in life; a devoted son, a caring brother, a husband in love, a protective father, a fraternal friend, a thoughtful poet, an excited student of the world around him. The gift he left us is the daughter who possesses his smile and is the is the living portrait of her father. Melisa Sayuri will one day learn that her father was an extraordinary and brave man.